Save the Blue Heart of Europe - A campaign for the protection of Balkan Rivers

Save the Blue Heart of Europe - A campaign for the protection of Balkan Rivers

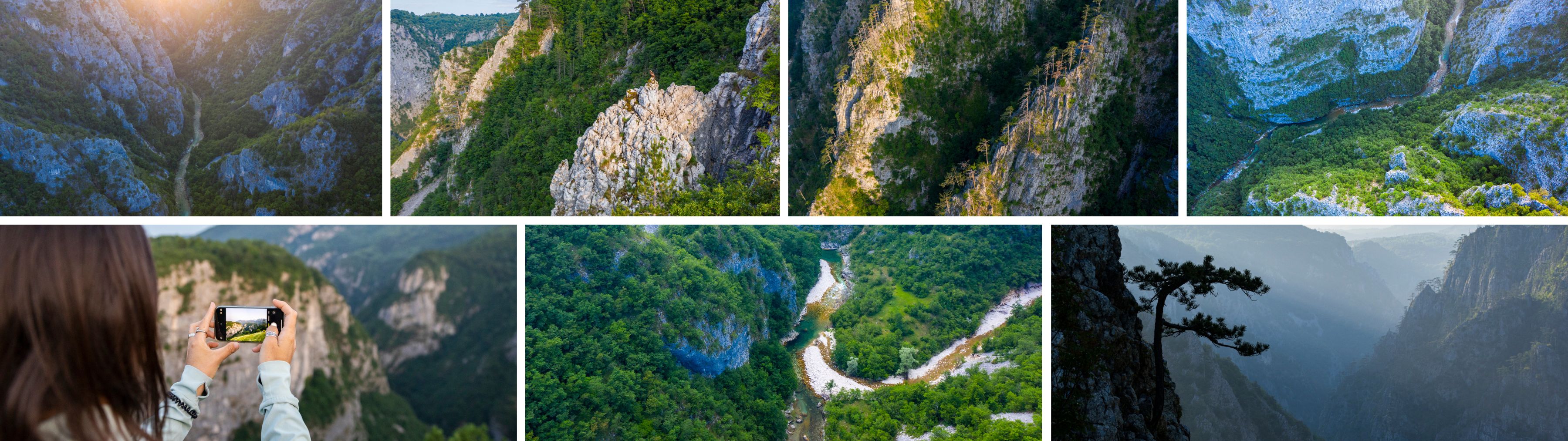

Komarnica Canyon through the lens

During the summer of 2025, photographer Bruno D'Amicis was tasked with capturing all the unique aspects that make Komarnica Canyon in Montenegro special. His expedition there reminds us of the many reasons this place is worth protecting. Read some of his notes from the field. Photos and words: Bruno D'Amicis.

The canyon of Komarnica: of cliffs, eagles and trees

The canyon of Komarnica: of cliffs, eagles and trees

I had never heard of the Komarnica until one year ago. It was in September 2024, at the Balkan River Summit held in Podgorica, when someone first told me about this unique river of Montenegro and its imperilled future. Towards the end of the event, I joined a short field trip to Komarnica and had the chance to descend into its narrow canyon. There, I could get a glimpse of its emerald-blue waters and learn more about the conservation campaign, led against the insane project of a large dam to be built near its end, which would mean that the whole area of the canyon and its ecosystem would be submerged under 100 meters of water.

Months later, the friends at the Montenegrin Ecological Society reached out, timidly asking me if I would be interested in undertaking an assignment to photograph this river and its unique features, to provide pictures in support of the conservation campaign: I didn't think about it twice and immediately said “yes”. And like that, early last June, I was travelling to Montenegro with a special assistant, my 9-year-old son Nils.

Montenegro is a small country, yet packed with stunning mountain ranges, canyons and gorgeous rivers, and the ever-increasing outdoor tourism is a clear response to its many natural wonders. Nevertheless, Komarnica remains a gem hidden in plain sight. Even getting a glimpse of it is not easy. The river flows between imposing cliffs that can reach up to 700m, and there are only a handful of (quite secret and rough!) trails which allow to reach it. No wonder that this canyon has been one of the last to be fully explored in Europe. Even today, only a few expert kayakers can claim to have seen it in its entirety.

On the evening of our arrival in the village of Donja Brezna, Nils and I immediately set off to a nearby hill to peer into the deep canyon at sunset. We were stunned: the view was both marvellous and terrifying. It was probably the exact same feeling, of attraction and repulsion, which early alpine climbers of the XIX century defined as “sublime.” The last sunlight was flooding the canyon. The river was glowing orange, while the grand limestone walls in the shade turned azure. Hundreds of large, centuries-old black pine trees were precariously hanging on cliffs and ledges, like silent witnesses. Two ravens flew by, and a black woodpecker cried in the distance. We felt inspired by peace and an upcoming sense of adventure.

And so it became clear that Komarnica was truly special. And in the following weeks, we came to appreciate it even more, discovering that it is a place for solitude and wonder. A place for bears and eagles and free people: in one word, a wilderness!

Komarnica underwater: a cold kaleidoscope full of life

Komarnica underwater: a cold kaleidoscope full of life

"Cold, damn' cold”, this is what I thought when I took the first plunge in mid-June. The waters of a mountain river are never warm, and the Komarnica makes no exception. Despite the warm temperatures outside, the river water was around 10° C, and I only had a short and thin wetsuit with me. Since the descent into the canyon is so long and tricky, and my photo equipment (including underwater housing) is so heavy, I could bring only the minimum. But as soon as I overcame the unease of the cold and the pull of the current, a breathtaking underwater scenery opened in front of my eyes. Beautifully carved stones and polished rocks of a yellow-ochre colour stood against the green-blue of the deeper water. Swift graylings and a few native brown trout bolted as I started making my way upstream.

The river was mostly flowing slowly, but in the narrowest parts, I had to cling to the rocks on its banks to overcome the increasing current. After about 400 metres of “river climbing”, I came to a small rapid. The canyon walls were almost perpendicular to the river at that point, and I couldn’t go any further, but peering into the dark depths of Komarnica, my eyes started noticing the shapes of the limestone cliffs going all the way to the river bottom: it was amazing to witness the canyon stretching into the underwater world. To my surprise, two large chubs emerged from a hollow rock and swam in front of me. By then, I decided to let go of my grip and swim downstream, back to where I had entered the watercourse.

When I let myself go with the stream of a river, an elating feeling of flotation and weightlessness always invades me, mixed with the thrill of avoiding logs and rocks, while trying to grab photos at the same time. I really enjoy this kind of underwater “street photography” and strive to document the fleeting interplay between light, colours, water and minerals as I swim by.

When I eventually reached a slower stretch of water, with sunlight in my face, an elongated shape suddenly appeared a few centimetres from my eyes. I got a little startled, but then I realised it was a very big dice snake, which I must have disturbed. It is a harmless snake, which feeds almost exclusively on fish: a common sight in the Balkan rivers. Still, this individual was one of the largest I had ever seen, and watching it swim in the blue, with its grey and black dorsal pattern, was a great sight that somehow reminded me of far more dangerous tropical sea snakes…

At a closer look at the river banks, I could see what attracted the dice snake: in the shallows, hundreds of minnows and young trout were finding shelter from predators. A few centimetres away from them, a plethora of caddis larvae and stoneflies were crawling on rocks, while scuds moved around the purple roots of willows festooning the shorelines.

I am always astonished by the sheer amount of life thriving even in a short stretch of a wild, healthy river. This is something most people ignore, and no speculator ever takes into account when making plans. I really wish people could experience what I witnessed. And this is why I do what I do and what I hope to convey with my hard-earned images!

Open habitats in Komarnica: the land of endless sunsets

Open habitats in Komarnica: the land of endless sunsets

The importance of Komarnica does not lie only in its clear waters and wild canyon. It also comes from the lush forests clinging to its cliffs, and perhaps even more from the dream-like open landscape stretching along its rims. A few small villages dot the region crossed by the Komarnica, between the town of Šavnik in the east and the town of Plužine in the west. The first is located very close to the mysterious canyon Nevidio (“Never seen”), which formally represents the beginning of Komarnica. While the latter virtually marks its very end, with the reservoir generated by the huge dam built in the 70s on the Piva river. Despite the low human density, the hillsides and plateaux encompassing the Komarnica canyon clearly show the effects of centuries of human presence.

Sheep husbandry and small-scale farming are still practised today, and their persistence over time has generated a complex scenery with beautiful open pastures, thick hedgerows and little woods surrounding rugged rocky outcrops. And in such a rich landscape, mosaic biodiversity thrives! During my assignment on those long June days, from sunrise to sunset, I was blown away by the beauty of the place. The vast fields were all in bloom: thousands of flowers of dozens of different species flooded the plains with yellow, white and scarlet colours, whereas tiny wild orchids, sober iris and fuchsia gladiolus peered among the most common plants.

Foxes, hares and roe deer timidly emerged from the woods at sunrise. Frogs and toads called from the shallow ponds. The song of skylarks, swallows and pipits filled the sky. Shrikes, hoopoes and buntings perched atop the flowering wild rose scrubs. Moving gently among the rocky patches, one could spot several lizard species, including the astonishing green lizard and the blue sharp-snouted one. And on a few warm mornings, we could even come across the intriguing horned viper. With its marvellous diamond pattern on its back and the fierce look, “Poskok”, or “jump” as it is named in Montenegrin, was surely one of the species ranking the highest on my shotlist for this assignment.

As the sun rose higher and the temperatures increased, I explored the oak woodlands, looking for other species. And while I looked for birds, I could encounter a hissing Aesculapian snake, a placid slow worm or a shiny stag beetle, and when I looked for insects, I found instead a Greater-spotted woopecker nest or a curious family of long-eared owls, living a short distance from our house. With such an amount of wildlife and the generous light of late spring, there was hardly any time to get bored!

Open habitats are becoming scarcer and scarcer across Europe. Change in land use, together with the abandonment of traditional practices, is favouring the return of woodlands, yet we risk losing some unique and fragile species. Places like Komarnica become extremely precious, something we cannot afford to lose. When a river is dammed and its path disappears under meters of murky water, not only is its flow affected, but the entire life thriving along its course is, too.

People and communities of Komarnica: village life

People and communities of Komarnica: village life

Despite its rugged, wild nature, the Komarnica region has been inhabited by humans for a very long time. Small, charming villages and single homesteads are spread all along the gentler slopes of the valley, just outside the canyon. Where modernity has not yet prevailed, the architecture remains exquisite, and the buildings typically have stone walls and tin roofs, often flanked by a large olm tree or a small orchard. Even public buildings like old schools or cemeteries maintain a similar general atmosphere and a strong sense of place.

Villages like Gornja Brezna or Bezuje, for example, are absolute gems in this respect.

Although some of these villages are not inhabited year-round, many houses belong to people living in the larger cities of Nikšić and Podgorica and who spend here weekends and vacations. During our assignment, together with friends at MES, we encountered several people who still live or work in the area and love Komarnica. Hospitality is still highly regarded in these mountains. Therefore, a glass of homemade fruit juice, or, more often, of rakija, always triggered open and engaging conversation. Translation was often needed, but sometimes I had to rely on non-verbal cues. And so, despite the language barrier, through smiles, expressions, and gestures, I tried to gather information about the territory's history and traditions.

One of these remarkable encounters has been the one with Mr Milija Ćeranić from the tiny village of Duži. This retired chemistry professor now spends his time in a tiny village, raising livestock and gathering edible and medicinal plants. His knowledge of the land and herbal medicine is combined with profound wisdom and remarkable ecological insight. Walking silently with Milija, his niece, and their cows was a profound and memorable experience.

On a sunny and warm afternoon, we took a long stroll with the shepherd Batrić Nedić, from Gornja Brezna, and together we followed his flock of sheep silently grazing across flowered pastures entirely yellow because of a galactic Lotus bloom. He told us about the ongoing depopulation of the area, the declining price of cheese, and encounters with vipers, bears, and wolves. Together, we could savour the smells of the pasture, the slow pace imposed by the flock, the last sunlight firing their fleece.